Published Date: February 7, 2024

A month ago, social media (LinkedIn and WhatsApp especially) were abuzz with an infographic which showed that Uttar Pradesh’s economy (as measured by Gross State Domestic Product, or GSDP), as a proportion of India’s economy (measured by Gross Domestic Product, or GDP) had overtaken that of Tamil Nadu—with Uttar Pradesh at 9.2 per cent, and Tamil Nadu at 9.1 per cent.

Various versions of this infographic (all of which were of questionable provenance, with unproven citations, and easily debunked as inconsistent with official Government (States, Union, or RBI) data invoked a lot of emotion and politicking.

I watched with amazement and amusement the extreme levels of absurdity and the absence of basic logic or understanding that surrounded the entire brouhaha—and kept my silence. I felt it best to avoid descending to the base level of most of the comments, despite requests from my friends to opine on the issue.

But with the passage of time and the fatigue of the propaganda machine (which has since moved on to other fake news and manufactured outrage), I felt it was important to take the time to say a few things on the topic, in the hope that it that might educate the public and help improve the quality of future debates.

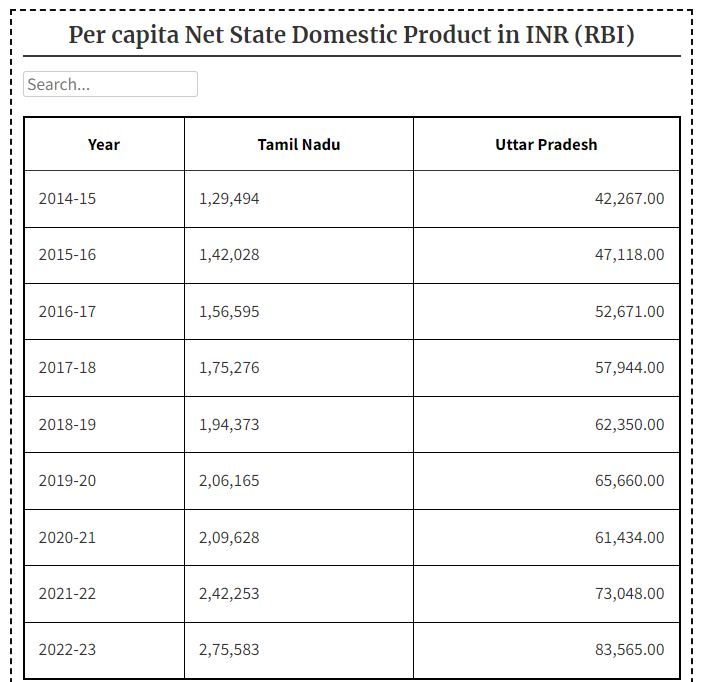

The data system in India is such that it is hard to state any year’s GSDP with any accuracy until more than 12 to 18 months after the close of the year, compared to about six months for countries like the US (a more detailed explanation of the Indian model follows). But from the available official sources of data, the GSDP of Uttar Pradesh was lower than that of Tamil Nadu for Fiscal Year 2022-23 (Uttar Pradesh—Rs.22.57 trillion (lakh crore); Tamil Nadu—Rs.23.64 trillion; Source: RBI) and is projected to remain so for the current Fiscal Year 2023-24 (Uttar Pradesh—Rs 24.39 Trillion; Tamil Nadu—Rs 28.3 Trillion; source: each State’s MTFP (Medium-term Fiscal Policy) statement presented in the 2023-2024 Budget).

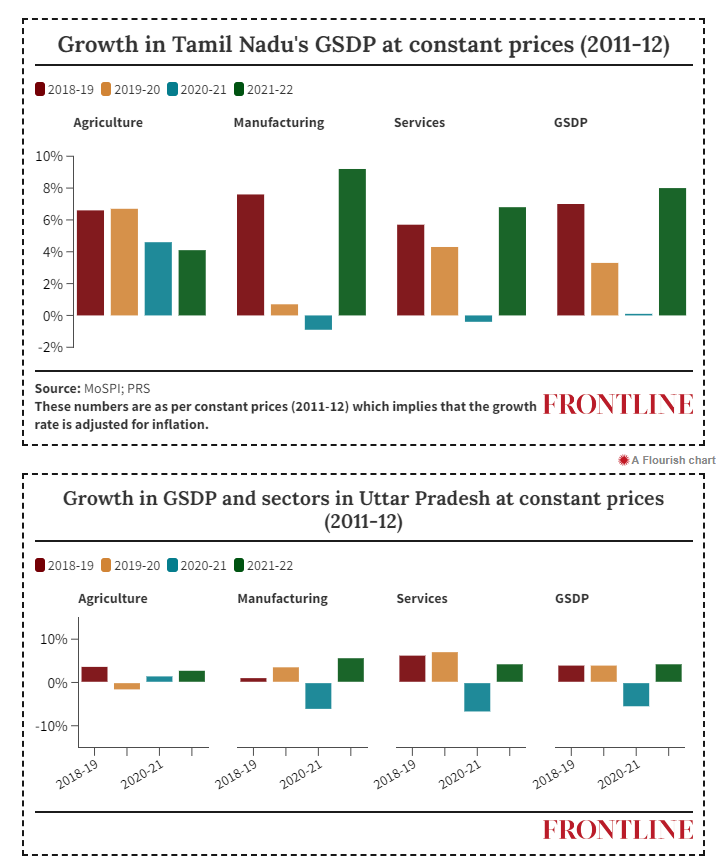

For the sake of countering the false narrative, we used current prices. However, a much more accurate measure of growth is to look at the growth rate at constant prices (after adjusting for inflation). As it turns out, Uttar Pradesh’s underperformance relative to Tamil Nadu continues, perhaps unsurprisingly, even considering GSDP at constant prices (source: PRS Legislative Research).

As I stated above, GSDP and GDP are notoriously hard to estimate given the data systems and models in our country. Each of these numbers released by the Central Statistics Office has at least five different estimates over time; it starts with initial estimates (Advance and Provisional Estimates), which are subsequently revised and released as the First, Second, and Third Revised Estimates.

The period for the estimates range from six months before to 18 months afterwards; these figures remain volatile, there are always huge jumps between any of these five estimates. This increase in volatility, the substantial lag in publication, and the loss in reliability may perhaps be attributed to this government’s propensity to suppress or avoid data collection as far as possible. This enables the propaganda machinery to proceed full throttle without the fear of facts or truth getting in the way, thereby allowing its preferred narratives to snuff out any substantive debate.

Recent articles even suggest the possibility of wilful manipulation of these estimates to tailor the numbers to suit the wishful thinking contained in the propaganda. Economist Arun Kumar recently called out the infirmity in the data and the invalidity of the method to calculate the GDP, arguing that the lack of accuracy in calculating the GDP was “vitiated due to methodological and data-related deficiencies” that suited the BJP’s “political narrative of a well-functioning economy”.

There is another basic flaw: the sum of the state-wise GSDPs usually adds up to 105-108 per cent of the national GDP. I have pointed out this flaw multiple times to officials of the Union Finance Ministry while arguing against the setting of hard borrowing limits based on such internally inconsistent data, especially in light of these models always erring on the side of less financial flexibility for the States (that is, each State’s borrowing limits set on a discounted GSDP, not the CSO’s own GSDP estimate). In effect, each year’s hard borrowing limit for the State set by the Union Finance Ministry is between 90 and 95 per cent of the FRBM and Finance Commission-ceiling-based borrowing limits calculated using the Union government’s own estimates of each State’s GSDP.

Compounding the unreliability of these numbers is the fact that we have not had a Census since 2011; therefore, the accuracy of calculating per capita estimates is inherently flawed. Coupled with the flaws inherent in the gross data collection, the per capita numbers now have large margins of error.

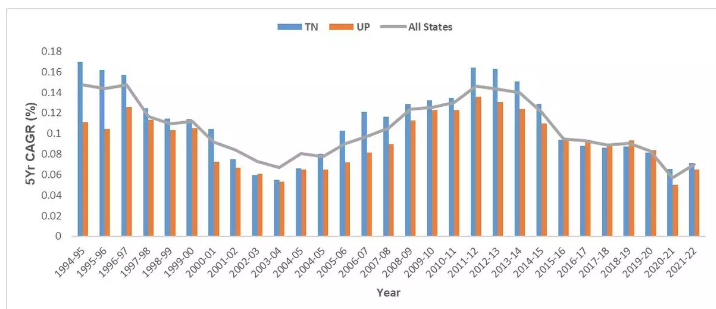

The actual growth rates (CAGR) in the graph below, based on nominal GSDP at current prices, going back 30 years, show that Uttar Pradesh has not outperformed Tamil Nadu, and, in most cases, not even as well as the national average.

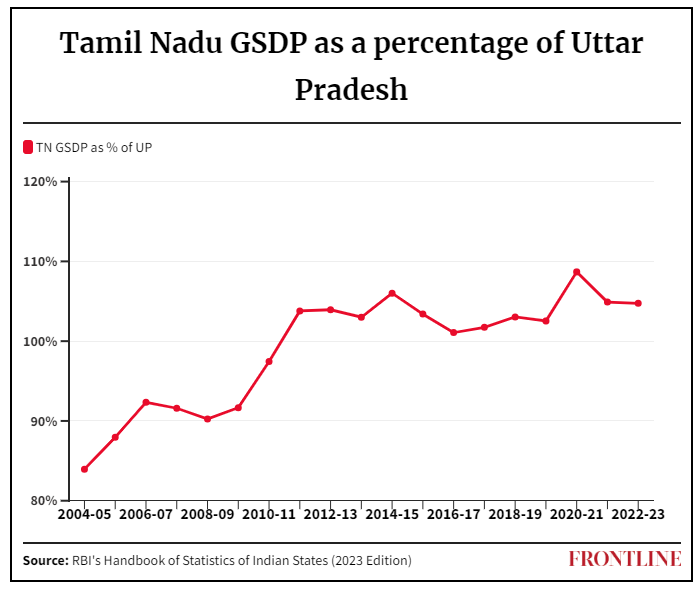

Two decades ago, Uttar Pradesh’s economy was 19 per cent larger than that of Tamil Nadu (2004-2005) and remained larger up until 2013-2014. It has only fallen behind as that of Tamil Nadu since the dawn of “Acche Din”, and was most recently 95.4 8per cent of Tamil Nadu’s economy (2022-2023).

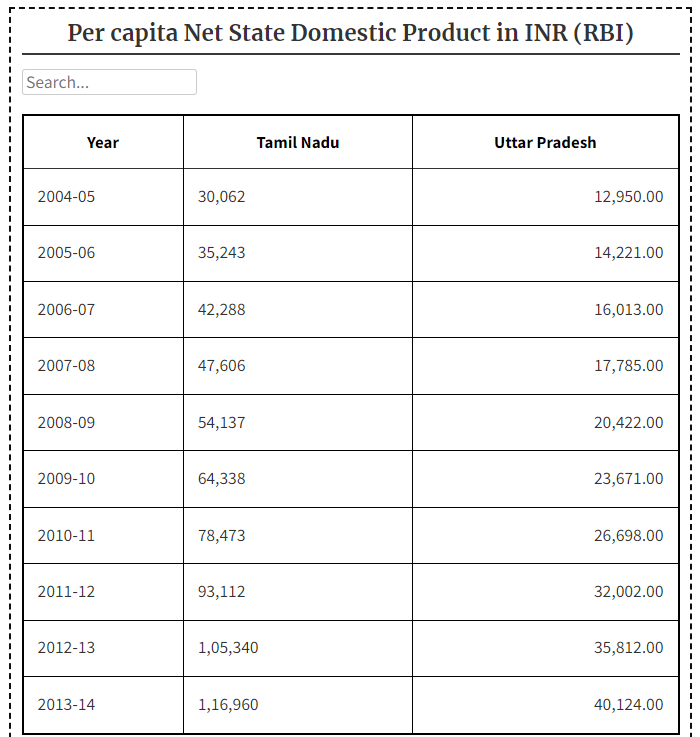

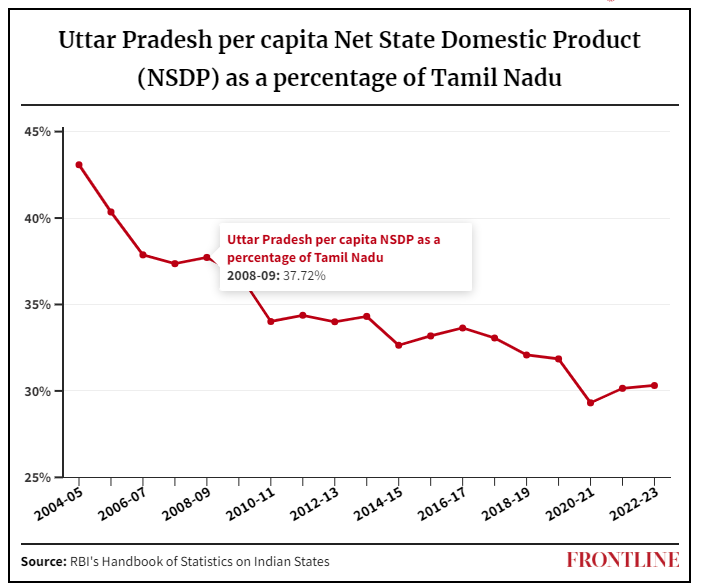

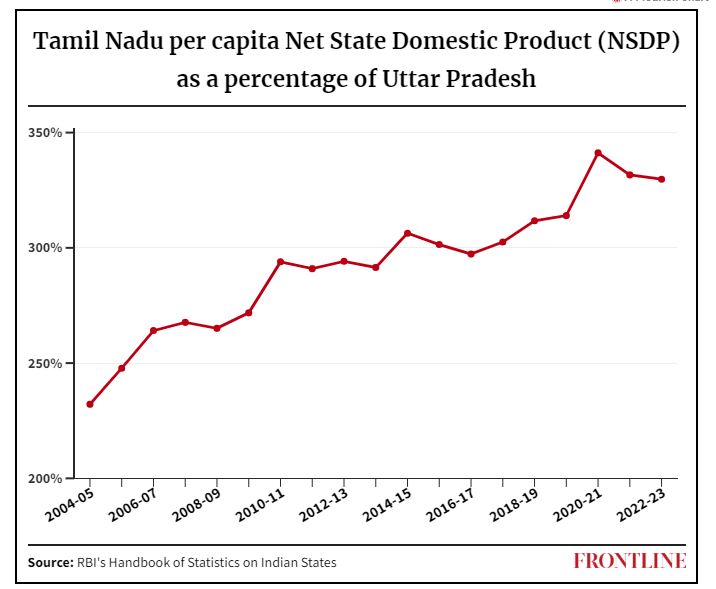

Though the GDP (national) or GSDP (State) is a reasonable measure of growth and development, it is not a reliable indicator of a region’s economic progress as it does not factor in the scale of the population, and hence says nothing about the average level of productivity or progress. In that respect, per capita productivity is a better estimate and a more accurate measure as it accounts for population size and wealth distribution. In this category, the average for Uttar Pradesh is a dismal one-third the level of Tamil Nadu, an almost continuous and steady drop from the 43.08 per cent of 2004-2005.

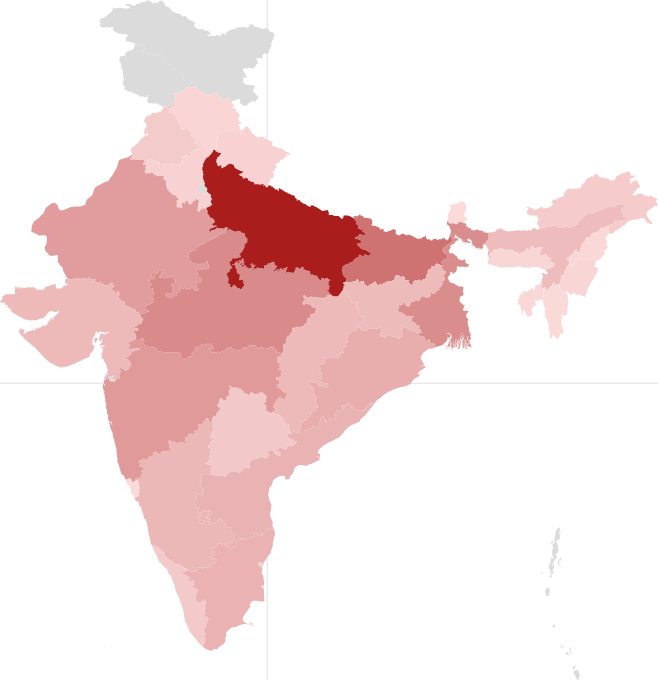

This disparity has persisted despite the natural tendency for higher growth at lower levels of economic progress (Uttar Pradesh), relative to advanced economies (Tamil Nadu). The continuous net transfer of tax revenues from better-off States such as Tamil Nadu to less developed States like Uttar Pradesh (much more needs to be said about this in future analyses) should also have resulted in the acceleration of growth in Uttar Pradesh to greater levels than that of Tamil Nadu—but it has not.

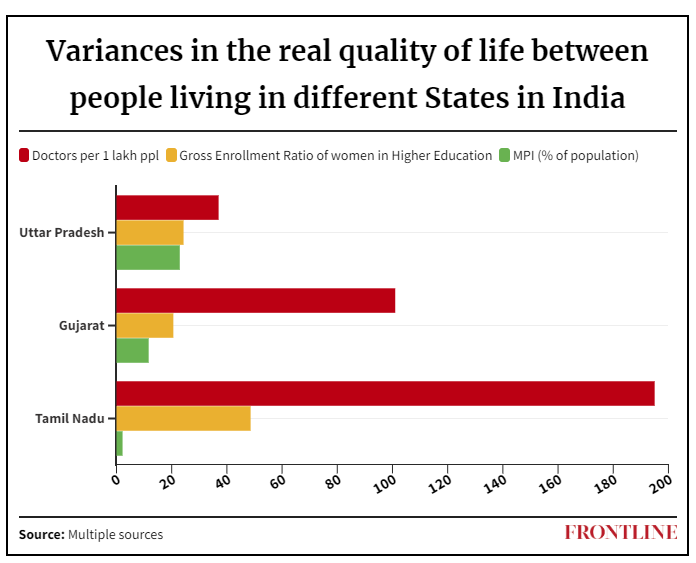

Even per capita incomes hide a lot of variations in the actual quality of life experienced by citizens of States with similar levels of income. Gujarat and Tamil Nadu have roughly the same per capita NSDPs (Gujarat at Rs. 2,50,100 and TN at Rs. 2,41,131 per the RBI). However, I have often invoked three quick parameters that reveal the huge variances in the real quality of life between people living in different States in India: access to health care, access to education, and multidimensional poverty index (MPI):

Perhaps not surprisingly given its relative poverty, all indicators are very poor for Uttar Pradesh. But it may surprise many to know of the massive advantage that people living in Tamil Nadu have over those living in Gujarat, in the context of health, education, and general progress. Consider, for example, the metric of the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). Many experts have been critical of the NITI Aayog claims that 24.8 crore Indians have been pulled out of poverty—labelling this a manufactured narrative in the run-up to the 2024 Lok Sabha election. Even under these numbers, only 2 per cent of Tamil Nadu lives in poverty compared to almost 12 per cent in Gujarat and almost 23 per cent in Uttar Pradesh. Despite being roughly equal in per capita income, those living under the Dravidian Model in Tamil Nadu fare much better than those under the alleged miracle of the Gujarat Model.

Perhaps it is not surprising then that Gujarat often leads in the illegal immigration racket; in the recent donkey-route plane with 303 Indians trying to illegally enter the US, 95 were from North Gujarat alone. Mahesh Langa’s in-depth report in The Hindu shed light on how the lack of opportunities and corruption in government appointments forced young people to undertake this nightmarish journey. It is to be noted that there was not one person from Tamil Nadu on the flight.

The lower the base, the greater the growth potential; this translates into the fact that the poorer the State is, the faster it can register growth, the greater its access to funds in the Indian Union, etc. This is the logic of why successive Finance Commissions in India have established a net transfer of funds from richer States to poorer States. The desired outcome of such spending is to ensure that high-population, low-income States grow faster than richer ones with smaller populations—and this is evidently something we want as humane citizens, from an altruistic perspective. It is rooted in the Dravidian ideology of social justice that we must reduce disparity and move towards equity. And we wholeheartedly believe it is in the interest of the unity of the nation that nobody should be left behind. This is why when Tamil Nadu receives only 29 paise for every rupee it contributes to the Union, and Uttar Pradesh gets Rs.2.73 for every rupee it contributes—we do not complain or begrudge it; we only lament that such largesse has not resulted in faster growth or equitable progress.

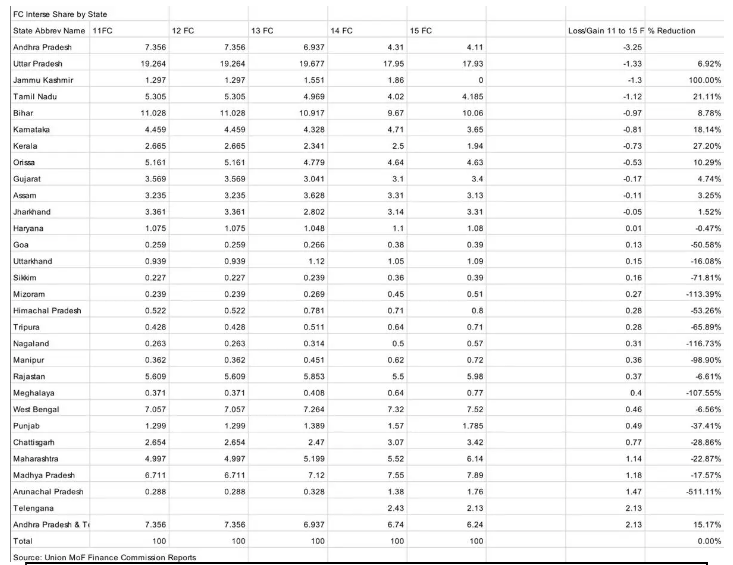

As we can see from the table given below, Tamil Nadu has lost 21 per cent of its allocation of Union funds over the past four Finance Commissions (20 years) as opposed to only a loss of 7 per cent by Uttar Pradesh.

Only when the GSDP of Uttar Pradesh exceeds that of Tamil Nadu, or becomes twice the size of Tamil Nadu, we can safely say that we are beginning to approach some sort of equity. The fact that the reverse is happening, with Uttar Pradesh growing slower than Tamil Nadu over the past two decades, even after huge transfer of funds from Tamil Nadu to Uttar Pradesh (through the increasingly skewed allocations of successive Finance Commissions, as well as the adoption of point-of-sale GST compared to point-of-production VAT & Excise) is an alarming trend from many perspectives. If we do not figure out a way to fix this issue, it bodes ill for the country’s future.

In my opinion, the single improvement that will yield the greatest results is to ensure greater inclusion and social justice in states like Uttar Pradesh, as is the case in states like Tamil Nadu—from education through participation in employment and entrepreneurship. It will take a generation for the benefits to be fully manifest. But it will yield lasting improvement. By contrast, all other steps are doomed to failure, unless this one is adopted.

All of the data cited above reveal the shallowness of those politicising the alleged change in economic rankings of Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, and shows the total absence of basic facts in the public debate that played out over the issue.

As I said, Uttar Pradesh’s economy was in fact larger than that of Tamil Nadu’s for years, possibly decades (the current RBI data series only starts with 2004-05). Considering that Uttar Pradesh’s population is now roughly three times that of Tamil Nadu’s, this is not only to be expected, but it should also be universally desired. So, the relative disparity on a per capita (adjusted for population) basis is even more startling. It is only in the alleged age of “Amrit Kaal”, when India has apparently been reborn as if all memory of the past was erased, that Uttar Pradesh’s GSDP “potentially” recovering to a size larger than Tamil Nadu’s is considered miraculous, and a sign of great governance of Uttar Pradesh or a failure of Tamil Nadu governance. Or perhaps both.

The less well-off falling further behind is not in the interest of any civilized society, as I have pointed out multiple time in discussions on the history of Union Finance Commissions and their failure to improve equity despite ever-increasing transfers from well-off to less well-off States.

Even in this Interim Union Budget for the FY 2024-25, we see that the entirety of the net proceeds of union taxes for the whole of South India is only ~Rs.1,92,722 crore, when compared to ~Rs.2,18,816 crore for Uttar Pradesh alone. That is, all five States of south India together were allocated only 88 per cent of the allocation made to Uttar Pradesh alone. I leave it to the readers to evaluate the fairness of such a skewed allocation.

The brief, polite answer is no. It is not surprising that the CAG report has highlighted how suboptimal the government’s management of finances and budget has been in recent years. The Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) pointed out a pattern of underspending between 2016-17 and 2020-21, with 20 per cent of the total budget provision remaining unspent in 2019-20. Not only did allocated money remain unspent, but the UP government did not bother giving utilisation certificates for money claimed to have been spent on welfare projects and for SC/ST (~Rs.6,000 crore).

Though it is not central to our thesis, and we are not in the business of commenting on the performance of other States, we simply point out that Uttar Pradesh has not been as well-managed as the propaganda machinery would have us believe, because the CAG data directly contradicts such a superiority of administration.

Given that Uttar Pradesh’s population at ~24 crores is three times more than Tamil Nadu’s population, even if its economy were to double, it would be poorer than Tamil Nadu per capita. At present, Tamil Nadu’s per capita NSDP is 320 per cent that of Uttar Pradesh’s. As a thought experiment, I have projected a scenario where Uttar Pradesh’s NSDP (CAGR of 7.6 per cent over the past 5 years) grows 2 per cent faster than Tamil Nadu’s CAGR of 9.47 over the past five years.

Granted that this is highly unlikely since Uttar Pradesh’s population is still increasing while Tamil Nadu’s is decreasing, the odds of a 2 per cent higher per capita growth, which would imply something like a 3-4 per cent higher gross growth, are practically non-existent. But for argument’s sake, let us assume this fantastic scenario becomes a reality. What then?

Well then… in 20 years, Tamil Nadu’s per capita NSDP would still be twice that of Uttar Pradesh’s. At an accelerated growth rate that is 2 per cent higher than Tamil Nadu’s every year, it would still take 64 years for Uttar Pradesh’s per capita net SDP to catch up with Tamil Nadu’s.

But why let such reality get in the way of a good story? The spin factory is hard at work trying to showcase UP as a success story, much like the hyped “Gujarat Model”.

Perhaps the real tragedy of our times is that the propaganda machine, arguably the most awesome and awe-inspiring in the history of mankind given the scale of India, devoid of facts, logic, reason, or even humanity. It obliterates the space for informed debate and thoughtful and humane discourse, which is so vital for a vibrant democracy and the foundation for informed policy to power faster and more equitable growth. It is a curse that the propaganda machine has removed every shred of intellectual content from the public discourse and darkened the environment into one filled with a cultish, vacuous, chanting of inane noise.

Palanivel Thiaga Rajan is Minister for Information Technology and Digital Services of Tamil Nadu.

Source: The Hindu