Published Date: December 28, 2016

Our family’s experience over a Century

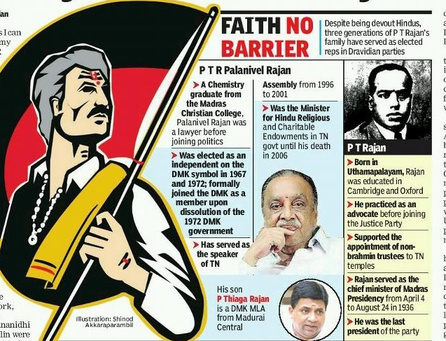

As far back as I can remember, my father prayed at the Meenakshi Amman Temple at least once a week. His faith was ever-visible on his forehead, including when he presided over the 11th Legislative Assembly of Tamil Nadu as its Speaker. In one of our last (telephonic) conversations before he passed away, he told me that his leader Kalaignar had offered him his choice of ministry in the cabinet formed from the 13th Legislative Assembly. He was picking the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments (HR&CE) portfolio, which his ancestors had been instrumental in creating. He had many plans for his term at the helm – but unfortunately, fate had other plans.

Up till that point, my own attendance at temples had been erratic – mostly because I had been at boarding school since the age of 5, and living overseas from the age of 21. But at that point, I committed to continue the family tradition of regular visits to the Amman Temple in honor of his memory, though monthly instead of weekly as I was an Investment Banker in New York.

Over the 10 ½ years since my father’s untimely demise, I have honored my commitment on at least 120 of the 126 months – accompanied by my family despite being based in New York, Mumbai and Singapore for most of these years. Both Kalaignar and Thalapathy M.K. Stalin were fully aware of these facts when they selected me this April to be the party’s nominee for the Madurai Central Constituency (which includes the Amman Temple, by divine providence). And I believe that my victory in the election – against the odds at least as far as the role of money was concerned – is due in part to the virtuous legacy of my forefathers, and to the Grace of Goddess Meenakshi.

I hope this personal information strongly refutes the Conventional Wisdom which implies that an anti-religious or non-religious stance is a pre-requisite for membership in the DMK – which is the 3rd generation Standard-bearer of the Dravidian Movement.

I believe the fundamental precept on Religion within the Dravidian Ethos has been unwavering over time – which is that (any) religion cannot be the basis for defining social status, that religious practices cannot require a social hierarchy, and that religious norms cannot be used to exclude, or discriminate between, people based on caste or gender (men and women are equal). In contrast, I do not believe the Dravidian ethos requires any religion-related litmus test for inclusion.

Though this core principle has stayed consistent over a century in my understanding, its manifestations in the realpolitik has changed noticeably during three distinct eras.

The early stages of the Dravidian movement (from 1916 till about 1937) was dominated by the Justice party and its legislative actions under Dyarchy. Many of the founders and leaders of the Justice Party were devout Hindus, who enjoyed a privileged existence based on their ancestral backgrounds and/or advanced educational/professional qualifications. Despite such privileged lives, the leaders of the party and the movement were – perhaps surprisingly – vehement supporters of the drive to democratize religion and its practices.

My great-grand-uncle Thiru M.T. Subramaniam (who headed our ancestral joint-family after the untimely death of my own great-grandfather) was a man of considerable standing amongst the Justice Party leadership, and instrumental in ensuring my grandfather Tamizhavel Sir P. T. Rajan entered electoral politics under its auspices. Both ancestors were then key players in the Justice Party’s introduction of The Madras Hindu Religious Endowment Act (in 1922), and its passage which resulted in the nationalization of temples in the Madras Presidency. Only true believers could have been so passionate about changing the way things were done – and legislating the equality they had espoused before forming the government. The subsequent (post-nationalization) efforts of my grandfather on behalf of many temples including the Vadapalani Murugan Temple, the Meenakshi Amman Temple, and the resurrection of Sabarimalai in particular, are well documented – and stand as testimony to the extent and depth of his faith.

In the second era of the movement, the interpretation of these principles took on a markedly more strident tone under Periyar and the Dravida Kazhagam. Periyar felt strongly that the gentlemanly approach of the privileged elite (the bulk of the Justice Party leadership) was incapable of bringing about much-needed societal change. Consequently, he opted for a radical approach to most matters, and fired the imagination of the masses with incendiary rhetoric. Phrases such as “Man before God”, and “Break Idols instead of coconuts (for the Idols)” gained currency.

However, it is important to note that even Periyar did not explicitly espouse Atheism. Instead he called for profound “Rationalism” in direct contrast to what he termed “Blind Faith”, especially from those who were oppressed. Periyar’s Wikipedia page includes an illuminating quotation – "...the talk of the atheist should be considered thoughtless and erroneous. The thing I call god… that makes all people equal and free, the god that does not stop free thinking and research, the god that does not ask for money, flattery and temples can certainly be an object of worship. For saying this much I have been called an atheist, a term that has no meaning".

In the third and current era, starting under the leadership of Arignar Anna, the DMK stepped back from Periyar’s incendiary rhetoric and confrontational actions – on several policy fronts. On religion, the rhetoric mellowed noticeably. Anna eloquently espoused gentler rationalist principles such as “Ondre Kulam, Oruvane Theivan (One humanity, Universal God)” using poetic phrases like “I break neither Idols nor coconuts for the Idols”.

Successive DMK governments have followed in Anna’s footsteps, and not wavered from the original Dravidian Ideal. As the undisputed leader of the Party for almost 50 years, Kalaignar has embodied these principles in both politics and legislation.

On the question of faith as a litmus test for inclusion or exclusion, my father serves as a good example of Kalaignar’s practice of the principles. At no point in his long career with the DMK did my father’s profound faith stand in the way of getting opportunities or positions.

I want to close as I began – using my personal circumstances to prove a point. On every visit to the Meenakshi Amman temple, we follow the same path that I first walked with my grandfather as a child, and then my father. It gives me immense satisfaction that my sons are tracing their ancestors’ footsteps each visit – and hope, that they will continue the tradition with their own children someday. However, as my forefathers did, we also have the Archanai recited in Tamil instead of Sanskrit– so we can understand what is being said, and it is therefore more meaningful to us.

And we remember every day that our right to believe, and practice, in our own way is what our forefathers and the Dravidian movement fought to ensure.